Why Hondo's near triple-double seasons were better than Oscar's

Guest post By Cort

Reynolds

It has become common

knowledge that Oscar Robertson once averaged a triple-double for an NBA season

back in 1961-62. This impressive feat has long been trotted out as

evidence that the Big O was the greatest all-around player of the pre-1980 era.

Robertson, in just his

second season, averaged 30.8 points, 12.5 rebounds and a league-best 11.4

assists per game. Incredible numbers, to be sure. He also shot 47.8 percent

from the field and 80.3 percent from the foul line.

Now, I am not one to

be overly impressed by someone merely getting a triple-double. I don't really

even like the statistic. I have seen too many overrated 13-11-10 triple doubles

by Earvin Johnson and Jason Kidd to just be blown away by a TD. If I get 30

points, 15 boards and nine assists, I don't get a TD.

But Johnson gets a

barely over 10 TD – like he averaged in the 1982 Finals – and with a generous

helping of hype gets a bogus playoff MVP over more deserving teammates Norm

Nixon and Bob McAdoo.

In 1981, Larry Bird

averaged just under 16 points and 16 rebounds a game in the 4-2 Boston win over

Houston and Moses Malone, despite being the focus of the Rocket defense,

especially tough Robert Reid, and the hub of the Celtic offense. And even

despite Larry's fine passing and game-high 27-point performance in the game 6

clincher at Houston – including a stretch of six points in a row late capped by

his dagger corner trey that finished off a Rocket comeback and quieted the

crowd - the pundits gave Cedric Maxwell series MVP. Hmm.

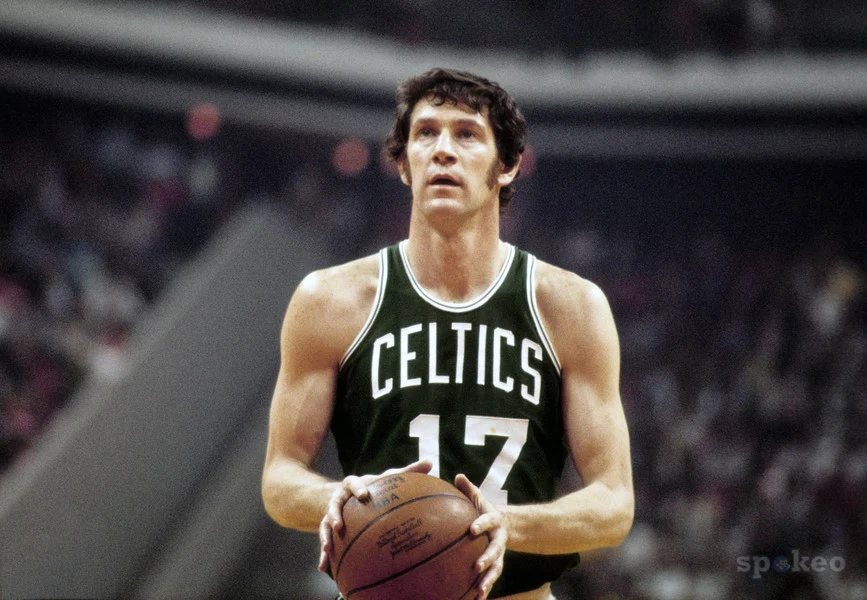

Anyway before I veer

too far off course, I am here to try and prove that quietly, and almost

unnoticed, former Celtic great John Havlicek had consecutive seasons in the

early 1970s that were better than Oscar's vaunted triple-double season. And

arguably the best all-around seasons in NBA history. In 1970-71, the 6-5

Havlicek averaged a career-best 28.9 points per game while also yanking down

nine rebounds a contest and dishing out 7.5 assists per game. He shot 45

percent from the floor and 81.8 percent at the foul line and missed only one

game as Boston finished 44-38. Very, very good but not as great as Robertson's

triple-double year, you might say? Maybe not quite as great statistically, but

then consider the other end of the court, where Hondo was probably the most

versatile and best defender in the NBA for much of his career. He was voted

second team all-defense that season, and was capable of guarding anyone from

small guards to big forwards with his quickness, tenacity, intelligence and

most of all, incredible endurance.

Havlicek made the

all-defense team eight straight years (five times first team, three times

second team) from the award's inception from 1969 through 1976, when he was 29

to 36. No doubt in his six seasons before the all-defense team was born, Hondo

would have made it at least five times. On the other hand, Oscar never made an

all-defense team. Ever. And was actually known as an indifferent defender. As

Bill Russell himself said on air during an ABC NBA telecast in 1972 courtesy of

NBA TV, “Oscar doesn't play much defense.”

Now the Oscar

supporters might argue that he had to do so much on offense that it was

unfair to expect him to be a standout defender. Maybe so, but Robertson

also monopolized the ball on offense and got more assists because he always had

the ball and was an excellent passer. In fact the biggest criticism of Oscar is

that he dribbled too much – one he answered by saying, ok, but I am the best

player on my team and thus should have it the most. On the other side, Hondo

excelled with and witout the ball. Havlicek, conversely, was mainly a forward

and as such didn't have the ball in his hands nearly as much. His 7.5 assists a

game as a forward are about as impressive as Oscar's 11.4 assists in his

triple-double season. And in 1961-62, teams took more shots and missed more per

game, allowing for more rebounds. Although Oscar was a guard, at 6-5 and 220 –

at least – he was bigger than Havlicek, and every other guard in the league by

a large margin. He got a lot of easy baskets by simply overpowering small

guards and shooting short jumpers over them. He was Earvin Johnson with a

better jumper 20 years earlier in terms of size compared to his peers. Havlicek

did not get such easy baskets in the halfcourt. His scoring game was moving

without the ball tirelessly, driving, 14-to 20-foot jumpers, running the court

with greater speed and endurance than Robertson. All while playing 45.4 minutes

per game. Plus Hondo was considered, along with Jerry West, as the best clutch

player of that time, at both ends of the floor.

In 1971-72, Hondo

averaged 27.5 points, 8.2 rebounds and 7.5 rebounds a game while playing

in all

82 contests for 45.1 minutes a night. He shot 45.8 percent from the field and

83.4 percent from the line, eight seasons before the three-point line came into

NBA use. He led Boston to a 56-26 record and the Eastern Finals, where they

lost to New York. In Oscar's triple-double campaign, Cincinnati was 43-37.

Hondo had stars in young teammates Dave Cowens and JoJo White in his greatest

seasons 1971-73, but Robertson also played with fine players like Jack Twyman,

Adrian Smith and Wayne Embry in his triple-double year.

|

| Keep your statue O |

I just think

Havlicek's seasons were a bit better because he was a far, far greater defender

than Oscar, and his offensive and rebounding stats were basically equal – and

maybe even better when one adjusts for the era and his position. Ironically,

Hondo has said that the best player he ever guarded was Robertson - “he just

didn't have a weakness,” said Havlicek, humbly. I doubt the proud Havlicek

would say that Oscar was better than him, deep down, all-around.

A group of five Hondo

clones would beat five Oscar's in a fullcourt game by out-running, out-shooting

and out-defending the Robertson's, in my opinion.

So why have Hondo's

great near TD seasons remained unheralded and all but forgotten, while Oscar's

TD is commonly known? One main reason is the over-reliance on statistics and

love of numbers in our stat-minded sabermetric era, and the tendency to put “triple-doubles”

up on a pedestal as THE standard for all-around excellence, even though it

doesn't take defense into account much if at all, and also is vulnerable to the

low-number stat line (12-11-10 is a TD while 35-20-9 isn't). That's simply

short-sighted and stupid. He merely missed a triple-double average by a rebound

and 2.5 assists in an era where there were fewer rebounds and when he didn't

have the ball enough to be able to compile 10-12 assists a night.

Even though he may

have been one of the earliest point forwards (long-time teammate Don Nelson

rescuscitated the term with Paul Pressey on the late 80s Bucks teams) – the

Celtics shared the ball handling duties and there were no such clearly

delineated positions then such as point guards and off guards. And believe it,

Hondo was an excellent, clever passer (6,939 career season and playoff assists

attest to that) who could thread the needle as well as almost any forward in

NBA history, just behind Larry Bird and perhaps Rick Barry.

Also, Havlicek was the

consummate pro who didn't seek the limelight or play in an era where the NBA

was marketed that well. He didn't have the ball all the time like Oscar, or

have a catchy nickname like the Big O, although Hondo is a decent moniker.

Basketball isn't a sport that is as easily captured in stats like baseball is.

A player's defensive value is rarely well-captured by stats. In fact, blocks

and steals are often compiled by guys who gamble a lot and don't play real good

defense (see Dr. J).

So much happens beyond

the box score, so much more than baseball. There has not been an adequate stat

for screens set, or box outs missed, or deflections, or hockey assists, or

stimulation of ball and player movement yet. Nor switches hedged or un-hedged

on picks, or screens called or uncalled. Boston lost a title in 1973 when

Havlicek, playing his usual intense defense, slammed into the stolid Dave

DeBusschere, who was setting a screen on Hondo early in their epic 1973 Eastern

Conference finals showdown. Celtic teammate Paul Silas failed to call out the

pick and when Hondo slammed into the 6-6, 235-pound DeBusschere full speed, he

injured his right shooting shoulder badly. As a result, Boston fell behind the

Knicks 3-1 without their superstar. Havlicek came back valiantly to help Boston

to wins in game five and six to extend the series to the limit. But the Knicks

broke open a taut seventh game in Boston Garden and stymied the injured Hondo

and Celtics to become the first team ever to win a game seven at Boston. And

this was in, ironically, the best season in terms of wins and losses in Celtic

history. Boston was 68-14 that season, the best record in franchise annals, yet

despite the 17 banners hanging in the Garden, that year the Celtics fell short

because of Hondo's injury. New York went on to beat the Lakers 4-1 to claim the

crown, and a healthy Boston almost certainly would have done so as well.

Chamberlain was immobile and in his last season at 36, West was in his

penultimate campaign, and forward Happy Hairston was out with injury for LA.

The Lakers had also said, especially Wilt, that they would rather play the

Knicks because he couldn't run with a young Cowens. In addition, Boston swept

the Lakers 4-0 during that 1972-73 regular season.

Havlicek was often

overshadowed by others on his own teams too, contributing to his relative

anonymity. In college, Jerry Lucas was the superstar who got the lion's share

of the credit as Ohio State won one NCAA title and made three straight NCAA

finals while going 78-6 from 1959-62. Havlicek was Robin to Jerry's Batman.

With Boston he started out as a sixth man and didn;t complain, unselfishly sacrificing

so lesser teammates could start. But even by his second year Hondo was second

on a championship team in minutes played, and was almost always on the court at

the end of the game, when it mattered most. In fact, in every season of the

1960s but one, Hondo's college and pro teams made it to the championship round

every year and won six NBA titles and one NCAA crown. But early on he was

overlooked because Boston had Cousy, Russell, Sam and K.C. Jones, etc. By 1969

he had become the star who led Boston to the last title of the Russell era. Yet

West, who was stupendous in a losing cause for LA, was named playoff MVP over

Hondo.

Not until 1974, when

Havlicek led Boston to the first post-Russell NBA title in franchise history at

age 34 and was named playoff MVP, did he finally get his just due. And by then

his prime was about at its end. John's style of play was very understated, he

didn't cause trouble off the court, he didn't do a lot of national ads or

self-promote like players of subsequent eras did. He was stoic and

self-effacing. Yet don't underestimate how great a competitor he was. Mot fans

know about his famous steal in the 1965 seventh game against Philadelphia. Not

many recall his nine-point overtime in game six of the 1974 Finals, or his

apparent running game-winner off glass in the three-OT classic fifth game of

the 1976 Finals – despite playing on an injured foot at age 36. College

teammate and backup Bob Knight mused on why Havlicek's star eclipsed the

considerable one of former college teammate Lucas in the NBA - he just wanted

to beat Lucas, Knight reasoned – demonstrating Hondo's dogged determination to

not lose, his quiet but indomitable pride.

A poor kid of

Czech/Croatian descent from the Ohio/West Va./Pennsylvania coal mining

panhandle, Havlicek had the humility, athletic ability, size and drive to be

truly great, and his unassuming personality made him universally respected.

Recruited by Woody Hayes to play football at Ohio State, he was a three-sport

all-state athlete who nearly made the Browns roster as a receiver when they

were the NFL champions. He won eight NBA titles and could easily have had three

NCAA crowns in three years with just a few breaks, instead of “just” one.

The

pivotal game four of the 1973 eastern finals at New York was telecast by ABC on

Easter Sunday that year (and re-broadcast a few years ago on NBA TV), with

Russell and Keith Jackson announcing. Havlicek sat out due to the right

shoulder strain, but was still announced by the legendary MSG PA man John

Condon in pre-game introductions as out with injury.

The Knick crowd then did something they would never have done for Bird in 1984 or 1990, or Pierce in 2011...they politely applauded Hondo, who was in streetclothes on the Boston bench. That's respect. Without Hondo and with league MVP Cowens fouling out late, the short-handed Celtics blew a big lead and lost a double overtime classic, 117-110.

In the mid-1970s, when Havlicek passed the 25,000-point mark against the Lakers in Boston Garden, the entire Laker team on the court came over and shook his hand during a short stoppage in play. Respect. In the 1978 All-Star Game, 76er guard Doug Collins voluntarily gave up his starting spot on the East squad for his retiring idol, John Havlicek. Much respect.

And in his last game against Buffalo in the 1978 season finale at the Garden, CBS broadcast the game and his halftime retirement speech, even though the Celtics were far out of the playoffs for one of the few times in his 16 seasons. Even more respect. For one of the few times in his long and storied career, the stoic Hondo showed some deep emotion to the public.

But I'd put his

1970-72 seasons up there above Oscar's more celebrated triple-double campaign,

and maybe as the best in NBA history. As Russell said in a 1974 Sports

Illustrated article on Havlicek, he called the tireless John “quite simply the

best all-around player in NBA history.” High praise, indeed.

I might also argue

that Larry Bird's mid and late 1980s seasons were as good or better than

Oscar's TD year, but that is for another article. As Hondo also said, had he

known Bird was coming, he would have stayed around instead of retiring in 1978

to play with Larry and possibly add to his total of rings. In his 16th and

final season, Hondo still averaged 16.1 points a game in 34 minutes a night.

Thus even though he would have been 40 by the end of Bird's rookie year, Hondo

still could have been a valuable reserve by 79-80, maybe even back full circle

to his early-career sixth man role – and his familiar role of NBA

champion.

Cort Reynolds is a

free-lance writer with 17 years of experience as a sports editor, newspaper

editor, and sports writer. He also was a college sports information director at

his alma mater for five years and is a lifelong player, student and historian

of the game. You can contact him at cdrada@wcoil.com to comment or ask him

questions.

alt="" data-uk-cover="" />

alt="" data-uk-cover="" />