CL Summer School 2017: The “Process” that was the old ABA

The Big Event of Sunday, January 15, 1967 would irreversibly, irrevocably, maybe even irreverently alter the face of professional basketball – way more even than the unprecedented dominance of that season’s Wilt Chamberlain-led Philadelphia 76ers, who’d won 41 of their first 45 games after knocking off Coach Russell’s men on their own home court that very day.

No, the ultimate domino fell into place not in a gym, but on a gridiron. When Lombardi’s Boys from Green Bay dispatched the Kansas City Chiefs in the Los Angeles Coliseum, up in smoke went the dreams and schemes – at least temporarily – of a California cat by the name of Dennis Murphy.

Now fret not the fate of the ever-resourceful Mr. Murphy, whose inventive fingerprints would be upon a wide variety of sporting ventures thereafter.

But nearly two years before that historic first Super Bowl, Murphy and a group of investors were attempting to bring an American Football League franchise to Orange County. The notion had gained enough traction by the spring of 1966 that Murphy et al proposed the novelty of an AFL pre-season doubleheader in Anaheim for mid-August.

Unfortunately for the Murphy group, the AFL owners received and accepted a more lucrative offer than expansion – a full-fledged merger with the older, more established National Football League.

Although disappointed, a born speculator like Dennis was hardly shocked … indeed his endgame from the start had been to benefit from the consolidation of the leagues, which he’d foreseen happening. His timing was just off.

So, what was a young prospective sports entrepreneur with some ready cash to do?

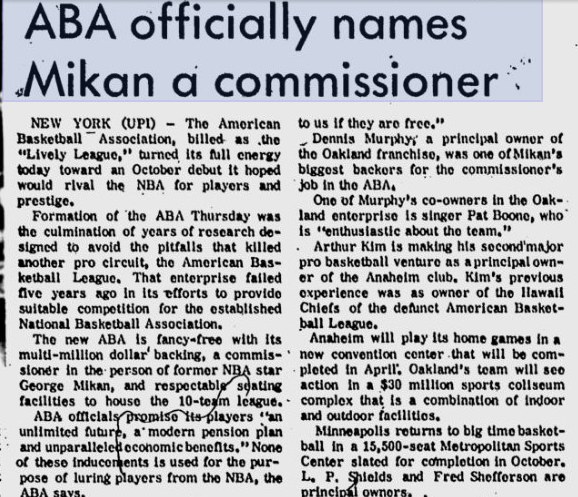

If you’re Dennis Murphy, you set about establishing the American Basketball Association. From the outset, the forward-thinking investor was anticipating a similar “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” union with the National Basketball Association in the not-too-distant future.

Who’d’a thunk that the ever-so-celebrated ABA – the league that provided opportunity to snubbed stars like Connie Hawkins and Roger Brown, that opened the doors to an early entrance to the pro ranks for college underclassmen like Spencer Haywood and Dr. J, that gave a chance to young coaching talent like Hubie Brown and even younger broadcasting talent like Bob Costas – was a business venture explicitly designed to fail, the sooner the better?

|

| The (Bend, OR) Bulletin, 2/3/67 |

In Murph’s own words, “We figured that within three years, we would be part of the NBA. Certainly by five years we would have either merged with the NBA or been out of business.”

His assessment was pretty accurate, too. By May of 1970, negotiators for the two leagues had hammered out a plan by which 10 ABA franchises – the status of the Virginia Squires, Murphy’s old Oakland franchise ironically, was uncertain – would join the NBA’s soon-to-be 17. The NBA’s Board of Governors officially approved the plan a year later.

Murphy had cashed in his ownership interest well before the time of this vote and was already conjuring up the World Hockey Association and World Team Tennis.

Maybe Dennis Murphy just anticipated what was going to happen next.

The resistance to the NFL-like merger came from the labor force … so the ABA, the league that was created so as to cease to exist, continued to fail in its mission – quite entertainingly if still in relative obscurity, it should be noted – for another five years until it simply ran out of money.

Oscar Robertson’s NBA Players Association, already challenging the “reserve clause” (a de-facto “team option” tacked onto the standard player contract of the day), added “illegal monopoly” to its list of jurisprudential gripes. Both the court system and the US Senate got involved. The Big “O” was virtually black-balled by the league for decades for his role in this legal wrangling.

As for Dennis Murphy, his future endeavors would include forays into Roller Hockey and Fastpitch Softball. He’d also take another crack at basketball too, launching a 6’4”-and-under summer circuit in the late ‘80’s called the World Basketball League.

Though my knowledge of the WBL is limited and sketchy, Murph’s summer league for little men did feature a dunking contest with a twist during its 1989 All-Star Game. The contestants competed in teams of two players. ESPN analyst and 1995-96 NBA Three-Point King-to-be Tim Legler collaborated with Youngstown Pride teammate Willie Bland to win. (I’d love to hear that story.)

The Enduring Impact

|

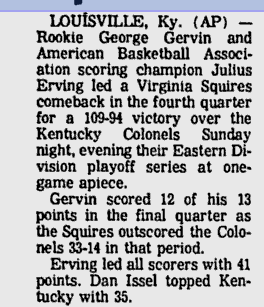

| Herald-Journal (Spartanburg,SC), 4/2/73 |

George turned pro at age 20, Julius was a babe of 22 that season.

As much as the ABA’s existence altered basketball’s salary structure …

As much as the ABA’s three-point-shot has recalibrated both the algebra and geometry of the game …

In 1966-67, the final season before the ABA’s launch, 123 players held a roster spot on one (or more) of the NBA’s 10 teams. Not quite one out of every six – 19, in total – was 30 or older. Over half – 65, in total – were 25 or younger.

|

| The Teenager |

In 1976-77, the first season after the ABA’s demise, 295 players held a roster spot on one (or more) of the NBA’s 22 teams. Not quite one out of every six – 45, in total – was 30 or older. Over half – 151, in total – were 25 or younger.

But the NBA of ’66-67 employed one player younger than 22 years of age.

The ’76-77 rosters featured 10 21-year-olds, three 20’s and one teenager (a second-year player, to boot).

[Also worthy of note from this roster comparison is a profound increase in player mobility. Our ‘60’s season saw a mere five guys compete for more than one team. A decade later almost 10 percent of the league – 29 players – had to re-locate, four of them twice.]

Recommended Reading

In an interview long after the fact, Larry Bird told Dominique Wilkins that his Hawk teams of the ‘80’s were simply too young to knock off Bird’s Celtics in a playoff series – and ‘Nique didn’t disagree.

That got me to wondering – when is a team no longer too young? at what point does it become too old?

In other words, just what is the optimal age for an NBA team with genuine championship aspirations?

Here’s the fallout from that episode of wonderment.

Murphy quote, background: Terry Pluto's Loose Balls

Background: "The Handle" Podcast

images: sportshistorycollectibles.com; amazon.com; northjersey.com

alt="" data-uk-cover="" />

alt="" data-uk-cover="" />