The 1970's Celtics: Overlooked Champions

In the fabled history of the Boston Celtics, buried between the long-term dominance of the Russell/Cousy/Jones 11-title era from 1957-69, and the opulent Bird/McHale/Parish epoch of the 1980's lie the frequently forgotten great Celtic teams of 1971-76. Partly because those Boston squads won "only" two league crowns, they have been banished to the back pages of the Celtic championship tapestry that hung up 16 banners over an unprecedented 30-year span from 1957-86. Thus by comparison their two titles - despite the fact that most other franchises would consider two crowns in three years, let alone over a decade, a major success and a golden era - come across as somehow underwhelming.

Taking on the personality of their quiet, self-deprecating superstar John Havlicek, the ironman bridge from the Russell era nearly all the way to the Bird epoch, the 1971-76 Celtics won consistently big in an understated, workmanlike fashion that does not lend itself easily to hype and rehashed heroics.

From the 1971-72 season through 1975-76, the Celtics made it to five consecutive Eastern Conference finals, and won it all in 1974 and 1976. Boston averaged a league-best 58.8 wins per season over that span and boasted the best record in the East each year as they posted win totals of 56, 68, 56, 60 and 54 in succession. Ironically, their title seasons came in the regular seasons where they won the least games: 56 in 1974 and 54 in 1976. Even more ironically, the year the Celtics registered the best regular season record in the storied franchise annals at 68-14 in 1972-73, Boston did NOT win it all.

The Celts lost to eventual champion New York 4-3 in the 1973 East finals, in large part because Havlicek missed much of the series with a severely injured shooting shoulder after running blindly into a rugged Dave DeBusschere screen in game three. Tom Heinsohn, the Celtic Hall of Fame forward who won eight rings as a player and two more as coach of Boston from 1969-78, called his smallish, hard-running 1970's Boston clubs "the quickest teams in Celtic history."

From 1971 to 1976, the speedy C's averaged 115.6, 112.7, 109, 106.5 and 106.2 points per game, ranking among the league leaders. Led by 1973 league MVP Dave Cowens, arguably the fastest center in NBA history, probably the greatest runner and constant mover without the ball in league annals in swingman John Havlicek and speedy guard JoJo White, the threesome formed as good a center/forward/guard trio as any in team history - and led Boston to perennial contender status with a breakneck, fast-breaking style.

Another thing that hurt the 1970's Celtics was that after Boston won 11 crowns in 13 years from 1957-69, fans were simply tired of the big Green dynasty. And just as Russell retired, a new and fascinating power was rising in New York, the media capital of the world, to supplant the Bostonians.

After years of also-ran status, the resurgent Knicks went to six straight East finals from 1969-74 after acquiring DeBusschere, and they captured the imagination of the basketball world with their cerebral and crisp passing, outside shooting game, as well as tough team and individual defense. Featuring such varied and interesting characters as the hard-nosed and skilled DeBusschere, the stylish Walt Frazier, Rhodes Scholar Bill Bradley, strong southern gent Willis Reed, flashy Earl Monroe, hippie Phil Jackson, memory expert Jerry Lucas, coach Red Holzman and others, the club won the only two NBA titles in the history of the franchise.

The colorful and charismatic Knicks became the new darlings of the league, the print media and ABC, which televised NBA games nationally (often featuring the big-market, big-ratings Big Apple squad) through 1973. The Celtics were forgotten and left behind, and didn't even make the playoffs in 1970 and '71 as Auerbach rebuilt the team into a new power.

|

| So many books, so few titles! |

Meanwhile by thriving in the media capital of the world, the great and interesting Knicks teams inspired dozens of books and a tremendous following at home and even on the road (and importantly, on TV) for their selfless, captivating style of play. As a result, more books have been written about the mere two Knick banners than the 17 Boston titles.

"So many books, so few titles," sarcastically observed one Celtic great in Harvey Araton's recent book called "When the Garden Was Eden," a book chronicling the fabled Knicks of 1969-74.

Boston and New York, the only two remaining original members of the league never to have moved from their birth city, carried on the traditional Hub vs. Gotham rivalry made famous by the Yankees and Red Sox, as well as by Rangers vs. Bruins and more recently by the Patriots vs. the Jets and Giants.

From 1972-74, the two ancient NBA rivals met in three straight memorable East finals, with the league's beloved Knicks taking the first two and narrowly leading in games won 9-8. The quality of basketball played between the rivals (featuring seven players in the 50 Greatest list) at such a high level of intensity and quality, as well as intellectually, has rarely been matched since.

Of course, had Havlicek not been hurt it's very likely that Boston would have won it all in 1973. The Celtics

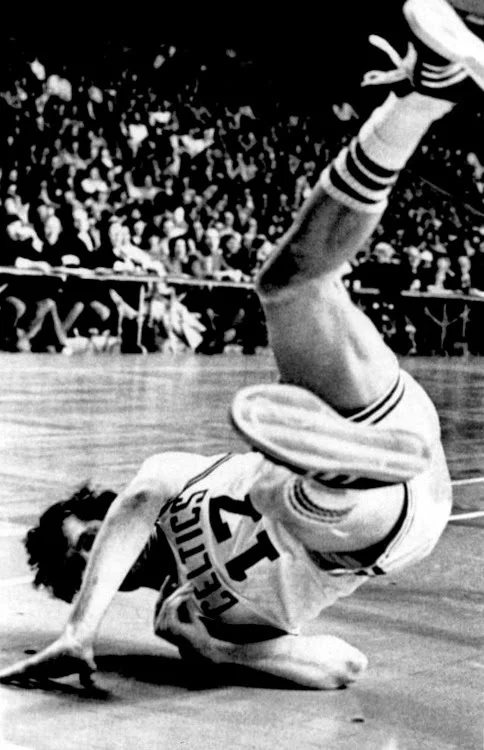

|

| Hondo's injury in '73 was devastating |

Boston finally broke through and beat the defending champion Knicks in 1974 by a 4-1 count in the conference finals, ending the relatively short New York dynasty. "If we were going to go out, at least we lost to a great team," said Frazier afterward. DeBusschere, Reed and Lucas retired and the New Yorkers were not a title contender again for 20 years.

But the Knick fever that enveloped the NBA in the early 1970's dwarfed the understated Celtics of that era.

Yet after finally getting past the rival Knicks, the Celtics faced another tall task in Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and the Bucks, who boasted the NBA's top record and thus had earned homecourt advantage.

In one of the best and most unpredictable championship series in NBA history, five of the seven games were won by the road team.

The teams alternated victories as Boston won games one, three, five and seven. But the best and memorable game of the Finals, true to the no-respect theme of the 1970's Celtics, was a double overtime thriller loss at home to Milwaukee when Boston was just seconds away from clinching their first world crown since 1969.

The signature play of the epic contest occurred late when Cowens, hedging out aggressively as usual on a screen vs. Oscar Robertson, poked the ball away from him. Stumbling initially from trying too hard to run after the ball, the 6-8.5 center still out-sprinted the 6-5 guard 40 feet for the ball, then dove headlong to grab the rolling sphere as an amazed Oscar ran up from behind.

A nearly 10-foot streak of sweat followed Cowens across the parquet floor, and even though he did not quite possess the ball as he slid to the sideline, the 24-second shot clock expired to give Boston the ball. This incredible play is still frequently shown on NBA highlights as an example of true grit and hustle in the biggest of moments.

Havlicek tossed in 36 points, including a record nine points in the second OT, punctuated by two rafter-scraping baseline rainbows over the flailing 7-2 Jabbar. The two teams traded baskets and the lead five straight possessions before a clutch Chaney steal led to Hondo's transition leaning lane follow shot of his own miss, which he banked in.

"My first shot was so bad that it surprised Kareem and bounced right back to me, and I made the second," said Havlicek, in typical self-effacing fashion. Havlicek's 11-foot rebound shot over Jabbar again seemed to give Boston a 101-100 championship-clinching win.

But after a timeout Jabbar tossed in a clutch, championship-denying running hook from deep in the right corner over backup center Hank Finkel (with Cowens having fouled out) to even the series, 3-3.

Going back to Milwaukee for a seventh game showdown in the final game of the great Oscar Robertson's career, the Celtic braintrust gambled an changed their strategy. They decided to front Jabbar and give Cowens a lot of help for the first time all series, since Dave was giving up nearly six inches in height and several more in reach to Kareem. Boston also decided to press the 36-year old Robertson, who was hampered by a leg injury, fullcourt to tire him out.

Standout defensive guard Don Chaney thus hounded Oscar 94 feet and disrupted the Buck offense. But Chaney got into foul trouble pressuring the Big O, and was replaced by talented second-year guard Paul Westphal. All Westy did was score 12 huge points off the bench and continue to harass and frustrate the Big O into a dismal 2-of-13 shooting performance in his swansong with great defense of his own.

Freed from the wearing shackles of playing Jabbar one on one, Cowens shone brightest in game seven. He used his superior perimeter game to drain several long jumpers. Then when the slower-footed Jabbar came out to contest Cowens, the fiery redhead blew by the laterally-challenged superstar for layups and running hooks by utilizing his much-better speed and quickness. Jabbar finally tired down the stretch under the swarming defense and relentless aggression of Cowens, and withered in the final minutes, leaving hooks and multiple free throws short.

A driving three-point play by Hondo, a long right corner jumper by Cowens and an improvised alley-oop form Westphal to Dave fueled a 10-0 run in the fourth quarter that put the game out of reach, and the hard-earned title on ice.

Cowens enjoyed his best game of the series with game-high totals of 28 points and 14 rebounds, leading the Celtics to a surprisingly decisive 102-87 road win. Havlicek was named series MVP after leading Boston to their 12th banner - AND long-awaited first without Russell - after averaging 26.4 points, 7.7 rebounds and 4.7 assists in the epic Finals.

At age 34 he had finally proved to himself and everyone else the former sixth man could win the big one without Russell (or Lucas in college), and was acknowledged as the best all-around player in the game.

Some knowledgeable observers even called the multi-sport star the best athlete in pro sports at the time, and they may have been right. "John is, quite simply, the greatest all-around player in NBA history," said no less an authority than Russell, in a Sports Illustrated article.

Supporting that strong assertion, from 1970-74 Hondo put together one of the greatest five-year stretches of all-around brilliance in NBA history. Averaging roughly 25 points, seven rebounds and seven assists per game in that span while swinging seamlessly between forward and guard, the 6-5 running machine also was named to the all-defense team every year.

The quiet son of a butcher who spoke only Czech at their rural Ohio home was the NBA's version of Lou Gehrig in many ways. He missed just 10 games in those five great seasons, six of those in 1974. One of the league's smartest players, he was also one of the most clutch players ever, as well as a superb passer and a dogged competitor. Separating himself from the ballyhooed triple-double season of Robertson, who was merely a decent defender, Havlicek was named all-defense the first eight years the NBA bestowed the honor from 1969-76, including five first consecutive team nods from 1972-76.

In the 1970-71 campaign, Hondo averaged a then-club record 28.9 ppg, nine rebounds and 7.5 assists a game while making second team all-defense. That all-around season stacks up with any in league history, but the rebuilding 44-38 Celtics just missed the playoffs.

He followed that year with 27.5 ppg, 8.2 rebounds and 7.5 assists in 1971-72, leading Boston to the division title and the East finals, where they lost to the Knicks, 4-1. In both seasons, he topped the NBA in minutes played at just over 45 minutes per game, and played 163 out of 164 contests.

In 1975, defending champion Boston tied Washington for the league's best record at 60-22. But in the Eastern finals, the physical Bullets pulled off a minor upset of the short-benched Celtics, 4-2.

The Bullets celebrated so much after winning game six at home that Red Auerbach noted they were emotionally drained/over-confident and thus despite being major favorites, were swept by Golden State and Rick Barry in the ensuing Finals series.

|

| McAdoo and Cowens |

The next season many thought the Celtics were too old to win another crown. Cleveland had risen int he East to take New York's position as the biggest obstacle to banner number 13, along with the tough Buffalo Braves.

As in 1974, Boston got by the Braves and sweet-shooting Bob McAdoo 4-2 in the eastern semis to reach their fifth straight conference final. But Havlicek injured his foot early in the series vs. Cleveland, and Boston was barely able to get by the Cavs 4-2 as the Ohioans were also slowed by a broken foot to star center Jim Chones.

Expected to face the defending champion Warriors, who led the NBA with 59 victories, the Celtics were given a reprieve. The upstart 42-40 Phoenix Suns, led by ex-Celtic Westphal and Rookie of the Year Alvan Adams, upset Golden State in a seventh game shocker by the bay to advance to the first championship series of their nine-year expansion history.

The teams each held serve at home over the first four games, with the Suns eking out a two-point win in game four when White's last-second jumper fell short to tie it, 2-2.

Then game the triple-overtime fifth game, often called the greatest game in NBA history. With the aging but ageless Havlicek back in the starting lineup yet still slowed by a foot injury, Boston ran out tto a 22-point lead. Yet the spunky Suns, playing with house money, slowly pecked away in half two, eventually tying it to force overtime at 95-all.

After one extra session it was still knotted 101-101. In the second OT, Boston appeared to win on a clutch Havlicek runner off glass from 14 feet out on the left side as time apparently ran out, 111-110. Delirious fans streamed onto the court and referee Richie Powers was slugged by a fan during the melee, probably for fouling out Cowens and waving off a key basket by the redhead moments before. However, after the court was cleared it was ruled that one second still remained, and the players were brought back out of the locker room after a fairly lengthy delay.

In the interim, Westphal persuaded Sun coach John MacLeod to take an intentional extra timeout to get a technical. White drained the shot after coming back on the court, having already taken the tape off his ankles in a prematurely-victorious locker room, to put Boston up by two. Yet after the technical, Phoenix got what it really wanted - the ball at halfcourt instead of 94 feet away, with a second remaining. Thus they had a much better chance to tie it in those pre-three point days of the NBA. And when Garfield Heard caught the in-bounds toss thrown past a leaping Jim Ard, he turned and quickly let fly over a straining Don Nelson from the top of the key.

Known for his high-arching, rainbow-style shot but not known as a good outside shooter, Heard's ICBM seemed to hang in the air for hours and nearly brush the bottom of the banners hanging from the Garden rafters before nestling softly into the basket as the buzzer sounded. The miraculous tying launch, which seemed to be a 30-footer due to the uber-high trajectory but was actually closer to only 20 feet, forced a third overtime.

With both teams running on fumes and a total of five key players and three Boston starters having fouled out in the marathon, the Celtics turned to little-used but well-rested backup guard Glenn McDonald.

All the unassuming McDonald did was score six huge points in the third OT to put Boston ahead, 128-122. Yet the Suns were not yet quite done. Westphal drove upcourt and tossed in a spectacular, running 360-degree midair banker from the left elbow. McDonald then mishandled an ill-advised alley-oop from Ard, Adams scooped up the loose ball and threw a bomb to Westy for a layup that cut it to two in the waning seconds. Pressing in desperation, Westphal almost stole a crosscourt pass and went flying out of bounds in the process. White dribbled out the final seconds near midcourt, then tossed up a tired 40-foot hook after the buzzer as the crowd rushed the floor again. JoJo had scored 33 huge points while playing all but five of the 63 minutes.

Across the country in Phoenix less than two days later, the two tired teams struggled to score. Boston led 38-33 at the half, foreshadowing the scores of the offensively-challenged NBA of the mid-1990's.

But former Sun Charlie Scott, who amazingly fouled out in each of the first five games of the Finals, was well-rested and came up with his best game of the series for Boston. Acquired in the deal for Westphal, Scott tallied his series-high 25 points in game six.

But it was Cowens who doused the Suns down the stretch by scoring nine of his 21 points. With a very close game hanging in the balance and saddled with five fouls, the hard-charging center let it all hang out, in the parlance of the era.

Cowens sealed Adams for a right-handed layup off a fine Silas feed. He drained a short turnaround jumper over Adams. Then he executed his signature move, a quick spin off the low right block to his left under and to the hoop for two more.

Capping his decisive run, Dave pulled off the clinching play of the game and series. As Adams drove to the basket, Cowens dangerously poked his hand in and dislodged the ball, even though a sixth foul would have disqualified him from the bout and thus made a seventh game much more likely.

The speedy big man recovered the loose ball, then rumbled upcourt like a runaway locomotive. As he approached the basket driving to his right across the lane, he subtly faked a pass to Scott to freeze the defense, kept the ball and banked in a beautiful reverse, overhead layup all while drawing a foul.

|

| Dave was ALWAYS all-business |

Such a play today would be replayed endlessly on the highlight shows and during the game. But back then, Big Red did not celebrate, as was customary with the no-frills, no theatrics Celtics of the 1970's. And he calmly drained the free throw to complete the play without any self-promoting antics or chest thumping.

"There are many players with great desire, but none play with greater desire than Dave Cowens," said Warrior great Rick Barry, who was serving as an analyst for CBS during the Finals after his championship team was upset by Phoenix the previous round.

The daring steal and three-point drive killed the Suns, leading Boston to an 87-80 victory and their 13th title. White (21.7 ppg, 5.8 assists, 45% FG) was named MVP of the Finals, but it just as easily could have been Big Red, who averaged 20.5, 16.3 rebounds and 3.3 assists per game while shooting 54 percent from the field in the classic series.

|

| Jo Jo and Pistol, two all-time greats |

Cowens and the indefatigable Havlicek drove the Celtics in the 1970's, but the underrated White was also an indispensable key. An All-Star every year from 1971-77, JoJo was a tremendous shooter, fine passer, solid defender and another, like Hondo and Dave, in great shape. Even in his 40's, White made a comeback with the CBA Topeka Sizzlers.

White is arguably the best all-around guard in team history, with Sam Jones, Dennis Johnson and Bob Cousy also in the running for that coveted honor. But JoJo was overshadowed by contemporary rival Frazier and upstaged by the charisma, play and wardrobe of "Clyde". The cleverly icy, mutton-chopped New Yorker's slightly greater play, great clutch performances and his big-city publicity machine earned Walt more ink than White's less hypnotic style. In an era laden with great backcourtmen like Jerry West, Frazier and Robertson in the early 1970's, White was simply overlooked. He also wasn't as flashy as other star guards of the era like Nate Archibald, Pete Maravich, George Gervin or even Westphal, nor as mercurial as Doug Collins or Calvin Murphy.

He was just extremely consistent, averaging 18-23 points and 4.5 to six assists per game from 1970-77, when age began to take a toll on him. And that sort of excellent consistency is often seen as boring or taken for granted after a while.

In 1974, with Boston leading Buffalo 3-2 in the East semis, White was fouled at the buzzer of a very tense tie game by McAdoo. As the only man on the foreign Buffalo court as the partisan Brave crowd screamed and stomped loudly, JoJo calmly drained both pressure foul shots to advance Boston to the conference finals, then ran off the court without much celebration.

AS CBS commentator Brent Musburger said late in game six of the 1976 NBA Finals, "In a franchise known for its great guards (Cousy, Sharman, Jones), JoJo White doesn't get the credit he deserves...he has handled the pressure well."

|

| KG will make the HOF but Jo Jo should already be in |

The fact that White has not been inducted to the Hall of Fame, while a fine guard who never even sniffed an NBA title like Mitch Richmond was recently voted in, seems a great oversight. Especially in view of JoJo's stellar play for America on the 1968 Olympic gold medal team, his standout college career at Kansas and his starring role in two NBA title squads.

Cowens epitomized the 1970's Celtics and was the second-best center of the decade (behind Jabbar) in an era chock-full of Hall of Fame big men. Starting in 1970, the unsung number four overall pick out of Florida State burst on the scene and was co-Rookie of the Year (with Geoff Petrie), rewarded ahead of more heralded rooks like Bob Lanier, Rudy Tomjanovich and Pistol Pete.

He was named to the 50 Greatest list in 1997 (along with Havlicek), was picked for eight All-Star Games, and was MVP of the 1973 mid-season classic. Over his first seven seasons, no one ever played harder at a higher skill level than Dave, who was also a very smart player. Willis Reed called him one of his favorite competitors to face, and no less an authority than Hondo said years later that "no one ever did more for the Celtics than Dave Cowens."

Heinsohn invented a new point center offense to take advantage of Dave's unique skills, hustle and athletic abilities. As fast as any guard, as strong pound for pound as anyone in the NBA and a tremendous leaper, Dave was not a great shooter when he first entered the NBA, a slightly better athlete than player.

But with practice he became a very good outside shooter, especially for a center, and became a great player. He drew bigger opposing centers away from the hoop to create driving lanes for himself and teammates. Cowens was also a fine passer and great rebounder who would get his 20, 15 and 5 regularly while shooting only just over 16 times a game.

|

| Dave was tenacious |

All while playing hell-bound, knee-scraping defense as the best center ever to switch out on screens and hound smaller guards. His incredibly quick and aggressive hedges became the scourge of NBA guards whose centers were unwise enough to set a screen for them, setting the smaller backcourtmen up for Dave's ferociously hard switches.

Upon his Hall of Fame induction in 1991, fellow inductee Bob Knight said Cowens was "one of the few players he would turn on the TV to watch." Cowens chose Bob Pettit, an NBA all-time great of similar size, skill and intensity, as his HOF presenter.

The Celtics of that era also boasted several other key players. Chaney was a tremendously long-armed defensive backcourt ace at 6-5 who teamed well with White. A smart player almost always under control, Duck started out as a poor shooter but became adequate as a marksman before leaving the Celtics as a free agent in 1975 for an ill-fated run in the ABA. He came back to the NBA with none other than the hated Lakers before finishing up back with the Celtics in 1979-80, making him the only man to play with both Russell (as a rookie in Bill's last season), and with Larry Bird in Don's final season/Bird's first pro campaign.

Don Nelson served as Havlicek's forward runningmate starter and then as a sixth man, alternating with Paul Silas in the famed Celtic reserve role, from 1972-76. A fine shooter who scored as many as 14 ppg, a solid passer and another very cagey player, he retired after Boston won the 1976 crown. Almost immediately became one of the NBA's youngest coaches when the Bucks hired him. Nellie molded the Bucks into a perennial contender which won seven consecutive Central Division titles from 1981-87.

The acquisition of rebounding ace Paul Silas for the 1972-73 season is what took Boston to the championship level, shoring up their depth and board work. The veteran was a fine defender, selfless teammate and one of the best rebounding forwards in league history, a huge upgrade over Nellie in that area.

He particularly was strong on the offensive glass, where he and Cowens relentlessly attacked opponents and the missed shots of teammates with abandon. Cowens was a great tip-shot maker, and he and Silas formed a reckless, physical and hard-working duo on the boards that no team surpassed in that era.

|

| Silas was relentless |

Silas was also a clever, high-intangibles player who although a mediocre shooter at best, could score just enough to keep defenses honest. And like all the Celtics of the time, he ran the floor well despite his muscular, big frame. His two clutch free throws at the very end of game 6 in the 1973 ECF vs. New York, with elimination on the line, gave Boston a 98-97 victory.

In his four seasons wearing Celtic green, the consistent 6-7 Silas averaged over 13 rebounds per game and just under 13 ppg. Boston won two rings and made it to the ECF all four of his seasons. When he left, they missed the ECF for the first time since 1971. In his last three NBA years as he approached 40, the heady Silas won a third title as the elder statesman of a young Seattle team in 1979, and came within a game of copping another crown with the Sonics in 1978.

|

| Paul Westphal |

Westphal was a high first round draft pick in 1972, but Heinsohn's reluctance to use much bench, let alone a flashy rookie, limited his playing time early. A fine passer, shotmaker and the most ambidextrous player of his time, Paul was also a smart, underrated defender with quick hands and fine leaping ability. The 6-4 guard particularly liked to dunk left-handed.

He became a strong bench contributor in Boston from 1973-75, scoring nearly 10 ppg in 1974-75. Thus his puzzling trade to Phoenix at 25 when Chaney jumped to the Spirits of St. Louis just as Westphal was about to blossom into arguably the NBA's finest guard from 1976-80, ranks as one of the most questionable trades in Celtic history.

Even though the veteran, streak-shooting Scott helped Boston win that 1976 crown, he was just starting the downside of his fine career. Charlie was a quick big guard at 6-6 and an explosive scorer, as well as an aggressive defender who often fouled out. He had good hands and a nose for steals as well. His clutch game 6 performance in the '76 Finals helped Boston clinch banner number 13, precisely what he was brought to Beantown for.

|

| Steve Kuberski |

Steve Kuberski was an underrated backup forward for eight seasons with the Celtics, playing on both title teams. But he may have been better known for playing second banana to Havlicek in some laughable "'Lectric Shave" commercials of the mid-1970's. Amazingly in the advertisement, the balls kept bouncing back to the shooting duo in perfect rhythm as they discussed the oft-unshaven and shaggy Steve's lackluster, perennial three-day growth ("Steve, your beard is just laying there") while they practiced mid-range jumpers in the ancient Garden. I guess they had some great backspin on those shots!

In 1976-77, the aging Celtics' second dynasty began slipping into decay. Sensing they need to get younger, deeper and better on offense, Auerbach gambled and for one of the few times, lost. He sent Silas, an irreplaceable cornerstone of the team's hard work ethic, to Denver in a three-way trade amid a series of moves that brought Boston the more talented but much more selfish UCLA bookend forward tandem of Sidney Wicks and Curtis Rowe.

| Charlie Scott |

His worn-out status seemed to serve as an exemplar of what was wrong with the NBA at the time; if the league's pre-eminent All-Star hustler was disillusioned with the game and burned out, the public figured something must be wrong with the league.

|

| Dave was front and center with Dr J in the NBA-ABA merger |

With West, Robertson, Wilt and other long-term stalwarts of the league recently retired, and marquee big-market teams like New York, the Lakers, Chicago and Celtics struggling after carrying the league in the first half of the 1970's, the league began to lose fans in droves.

Cowens was one of the few symbolic bridges to the new ABA-merger era NBA expected to carry on the fundamental, old-school style of play most of the paying public appreciated. Now it appeared he was done too, and the fans did not appreciate the sea change taking place.

Wicks, in particular, affected team chemistry negatively as the club aged, Heinsohn raged and Hondo returned to his sixth man role at 37. Still, led by White and the return of Cowens, Boston squeaked into the playoffs at 44-38 and swept the Spurs in a first round mini-series, 2-0.

In the eastern semifinals they faced a familiar heated foe in the younger, hungry and star-laden 76ers of Dr. J, Doug Collins, George McGinnis. Philly's wildly eccentric bomb squad of characters featured no-conscience gunner Lloyd (later World B.) Free, dunking teenager Darryl Dawkins of Lovetron, ex-All Star Steve Mix and Kobe's dad, journeyman Joe "Jellybean" Bryant.

The not-as-deep, older Celtics won game one in Philly on a clutch baseline jumper at the buzzer by JoJo White. The rivals battled on to a seventh game, where streak-shooter Free (scoring 27 points off the pines) broke open a defensive struggle late by hitting several long jumpers as Philly held on for an 83-77 win that kept Boston from a sixth straight ECF showing.

Fans rushed the Spectrum court and the 76ers celebrated as if they had won the title, so big was beating the hated defending champion Celtics. Hondo scored 13 points in the 172nd and final playoff game of his career.

After getting past Houston, Philly almost did win that elusive ring, but the Sixers came up short against Portland and another fundamentally-sound, intense and athletic red-headed center in Bill Walton in the championship series, 4-2.

An aging Boston would not contend again in the so-called "me" decade, however. Havlicek retired one year later in 1978 after a depressing 32-win season that ended well short of the playoffs for just the fourth time in his 16 glorious seasons, eight of which ended up in the champion's circle. The 1978-79 campaign was even worse, starting 2-12 under Satch Sanders and ending up 29-53 under player-coach Cowens.

A few years later, Hondo lamented that "if i had known this Bird kid was coming, I would have stayed around a few more years to play with him." White was unceremoniously dealt to Golden State, and finished up with Kansas City, near his hometown of St Louis. Cowens, hampered by a recurrent nagging foot injury, retired in the fall of 1980 after one more great 61-21 season in Bird's rookie campaign that ended up in a disappointing ECF loss to the 76ers. Unfortunately for he and Maravich, who also retired during that 1980-81 pre-season, they each missed out on one last title the following spring.

The muscular southpaw made a brief comeback with Milwaukee under his buddy Nelson in 1982-83 after Boston traded him for Quinn Buckner, then retired for good. Milwaukee swept the Bill Fitch-mutinying Celts 4-0 that spring in the post-season, but Dave was sidelined by injury, hampering one of Milwaukee's best title chances of the Nellie era.

However, as an assistant coach for the Spurs in the mid-1990's Dave almost came back again as a player when San Antonio was decimated by frontcourt injuries. Few who knew him doubted that the athletically-gifted and driven Cowens could still have played in a reduced reserve role, even in his mid-40's.

Heinsohn was let go in 1978 after a nine-year run and 474 total wins, replaced by former teammate Satch Sanders and then Cowens for 68 games (27-41). He later went on to an excellent announcing career with CBS and the Celtic network, where he remains to this day.

Curiously, although five of the 1974 NBA champion Celtics went on to become head coaches, none became full-time head coaches of Boston. Surely, timing had a lot to do with the shutout, but one wonders if there were not bridges burnt with team patriarch Auerbach. The blunt, outspoken Cowens was openly critical of the Silas deal and then ended up coming back with the rival Bucks after a deal with the Suns fizzled.

Nelson angered Red by calling Danny Ainge a "dirty player" in the 1983 playoffs and had three heated series against the Celtics, and his long run with the Bucks ended after a gut-wrenching game seven loss at Boston in 1987.

Silas served as an assistant coach for the hated Knicks in 1990, when New York rallied to upset Boston 3-2. Westphal nearly led Phoenix to a title upset of the Celtcs in 1976. Chaney also coached the Knicks, albeit much later, along with the Rockets and Clippers. Like Nellie, who won the Red Auerbach Coach of the Year Award three times, Duck won it once with Houston.

But other than the unsuccessful 68-game player-coach tenure of Cowens in 1978-79, none of the great Celtics of the '70's ever served as coach of Boston.

|

| Curiously none of the 70s Celts, including Don Nelson, would go on to coach in Boston |

Nelson guided great teams in Milwaukee and Dallas, and fine clubs in Golden State as he became the all-time winningest coach in NBA history. But the luck that helped him win five rings as a Celtic escaped him as a coach; his great Buck teams were always thwarted by the 76ers or Celtics in the great East of the 1980's, and his best Maverick and Warrior teams were shut out by injury, bad luck and playing in the much-improved West of the 1990's and 2000's.

Cowens had a solid stint as Charlotte head coach in the late 1990's, and then unselfishly resigned so runningmate/assistant Silas could take over. Paul also coached the Clippers and Cavs in a solid post-playing career.

Westphal took the Suns to the 1993 Finals in his first season as Phoenix head coach, where they lost to the Bulls but won a triple-OT third game, making him the only man to play and coach in a three-overtime Finals contest. Westy also coached Seattle and Sacramento, was an assistant in Dallas and guided Grand Canyon College to an NAIA national title.

The ironmen Celtics, having made it to five straight conference finals despite a short bench, almost wheezed their way to a last title in 1976. Well before the Bird era, the team was probably on its last legs, featuring an injured Havlicek at 36, Nelson in his last season at 36 and Silas well into his 30's. Even White and Cowens, who were nearing 30, seemed older because they played so hard and so many minutes so deep into the playoffs every year, all of which made this incredibly hard-working team old, hurt and tired (sounds a bit like the Celtics of the late 1980's).

The Heinsohn-coached Celtics did not use their bench much in this era, playing seven players mostly. Their core players rarely missed a game, pushed the ball incredibly hard and battled as ferociously as any era in club history, epitomized by the fierce Cowens and the relentlessly running Havlicek.

They were not as glamorous as the Bird-era Celtics, nor as consistently championship-level for as long as the Russell teams, who incredibly won every title but one in the 1960's NBA. But that league featured just eight and then later, 10 teams. In the 1970's, the league had more good teams and improving front offices/franchises who learned from the Celtic dynasty and hungered to beat Boston even more to make up for their dominance over the previous decade-plus.

|

| The 70s Celtics |

In this parity-driven decade where no team repeated as NBA champion, one of the best epochs in league history unfolded as the great Knicks, Lakers, Bucks, Warrior and Celtic powerhouse clubs shared the title while fighting off many fine Bullets and Bulls teams.

The unspectacular but greatly-conditioned, relentless running Boston squads of Hondo, Big Red, JoJo and Heinsohn were a truly great team for six seasons, making the two-time champions the most underappreciated flag-winners in franchise history.

By Cort Reynolds

Cort Reynolds is a free-lance writer with 17 years of experience as a sports editor, newspaper editor, and sports writer. He also was a college sports information director at his alma mater for five years and is a lifelong player, student and historian of the game. You can contact him at cdrada@wcoil.com to comment or ask him questions.

alt="" data-uk-cover="" />

alt="" data-uk-cover="" />